The Hunt, Chapter 11: Overactive Gag Reflex

Some things can't be cured by practicing with a toothbrush

This is Chapter 11 in The Hunt, our ongoing serial. Read the Chapter 10 here.

Jurors take their roles seriously. They listen. They consider. They think. They reason. And they try very hard to find the truth, amid a mass of conflicting facts and testimony, armed with carefully negotiated, argued-over bits of law and instructions given to them by the trial judge, before they return to the jury room – usually the drabbest1 conference room you can imagine – to deliberate, sometimes for hours, sometimes for days.

While they do, the lawyers for the parties usually stay close.2 Not just because attempting to do any other work while the jury is out is futile, but because occasionally, juries have questions. And when a jury has a question, the response is as carefully debated and negotiated as the initial instructions.

Doug Mouser’s case was a difficult one. The jury deliberated for more than a week. After days of deliberations, the jurors had a question. They wanted to visit the location where Genna’s body was found3. They’d been taken for a view during the trial, and wanted to see the scene again.

Mr. Mouser’s counsel was ill. He participated in the conference with the judge by telephone, and assented to the “rules” given to the jurors, for their return to the scene.

The return visit was conducted in the presence of the prosecutor, but outside the presence of Mr. Mouser and his counsel. There was no court reporter present. There is no direct record of what occurred during the view; it’s known that some jurors descended into the ravine, and took notes on their experiences; they wanted to “test” the testimony of witnesses.

The jurors returned a guilty verdict after the scene inspection. Mr. Mouser appealed. His counsel sought out the jurors in order to develop a statement4 concerning what occurred on that second visit.

Gagging A Jury? Is This a Thing?

“...on top of it, they gagged the jury and I couldn’t interview any of the jurors to help Doug prepare for appeal,” the experienced private detective, Joe Maxwell, exclaimed into the phone to me.

“Is that not a thing?” I asked, interjecting.

“First and only time in the many years I was a PI, that it happened. You always interview the jury after a trial so that you can understand what went right, what went wrong and to prepare for appeals,” Joe explained patiently.

Now, he had my attention. In the land of weird-redactions of maps, exotic junk science and superhuman body tossing, we now had yet another first: jury gagging. Time to call my ornery New Englander.

–

Justin asked if I’d ever heard of an order prohibiting contact with jurors after trial.

I had, but only once. I worked on a case where an involved party had some criminal history. Years prior to any encounter with my client, the gentleman at issue had served federal time for some white-collar crimes.5 After his trial, before reporting to prison, he’d called a juror to ask why she’d found him guilty. He felt like they’d had a connection. Really thought she’d understand where he was coming from.

The federal judge to whom the panicked juror reported the contact was not so understanding.

Apart from that, I hadn’t heard of anything like that.

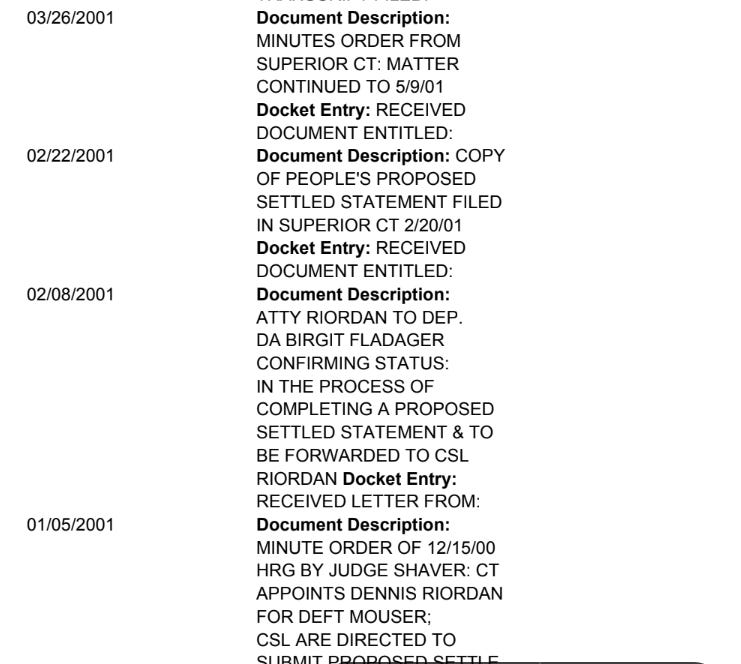

Stanislaus County is not a paragon of transparency. There were a few post-trial entries on the docket which could have been hearings or motion practice; it was hard to tell whether any were a gag, or protective order.

Looking at the public docket, and the dates we could glean from habeas and appellate filings, there were a few possible dates – but nothing worth sending a court clerk6 into a damp basement.

We had some boots on the ground in Modesto at the time, and thought running down the gag order might be worth the effort.

Unfortunately, not even the clerk could find it, without a more precise date. The court records ran into eleven volumes. She did, however, give us – or our boots – something absolutely lovely.

A list of docket entries. Full. Complete. With descriptions. A gift. A thing of great beauty. If we could tell her where to look, we could get the order.

…

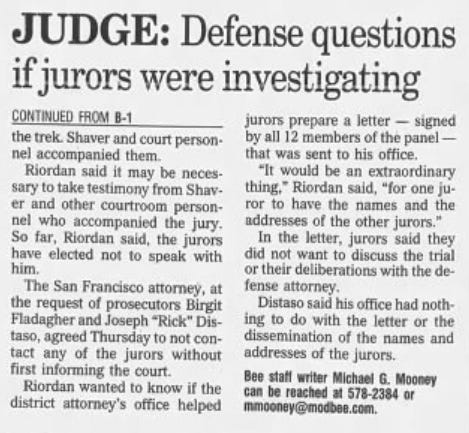

Modesto Bee, March 23, 2001 - https://www.newspapers.com/image/694352311/

Between the articles, and the docket entries, we were confident that we could tell the clerk where to look, without wasting her time.

We thought the order must have been entered somewhere in here:

And it was.

Usually not even a poster. Just in case that “Hang in there, baby!” kitten somehow ended up relevant to the topic at hand, and accidentally influence deliberations.

At my last trial, I alternated between the courthouse bathroom and the donut shop/Dominican take-out place across the street. My co-counsel favored the maple frosted; I liked the empanadas. I regret nothing.

Who wouldn’t?

In theory, every bit of testimony, argument, and instruction from a trial should be recorded by a court reporter, in a transcript equally available to both sides, and every exhibit or bit of demonstrative evidence should be marked by the reporter as well. That’s the record on appeal.

Where there are things that can’t be recorded properly on a transcript, or marked as exhibits, the way that can be dealt with is by some stipulation or settled statement about what occurred.

Remember what I said about investigations being impressive to clients? “Who the heck is _____ ?” being met with “Super shady. He defrauded a mom and pop manufacturing company, then after he was convicted, this fucking guy…” It’s easier than card tricks and sometimes you can bill for it.

The time, attention, and patience of court clerks is a precious and limited resource. And their memories are long.