Chapter Four in our series A Strange Love game - read Chapter Three here.

The "Medina Modification Center Explosion" took place on November 13, 1963, and it was no small event—destroying property, injuring workers at the Air Force base, and convincing some that World War III had begun.

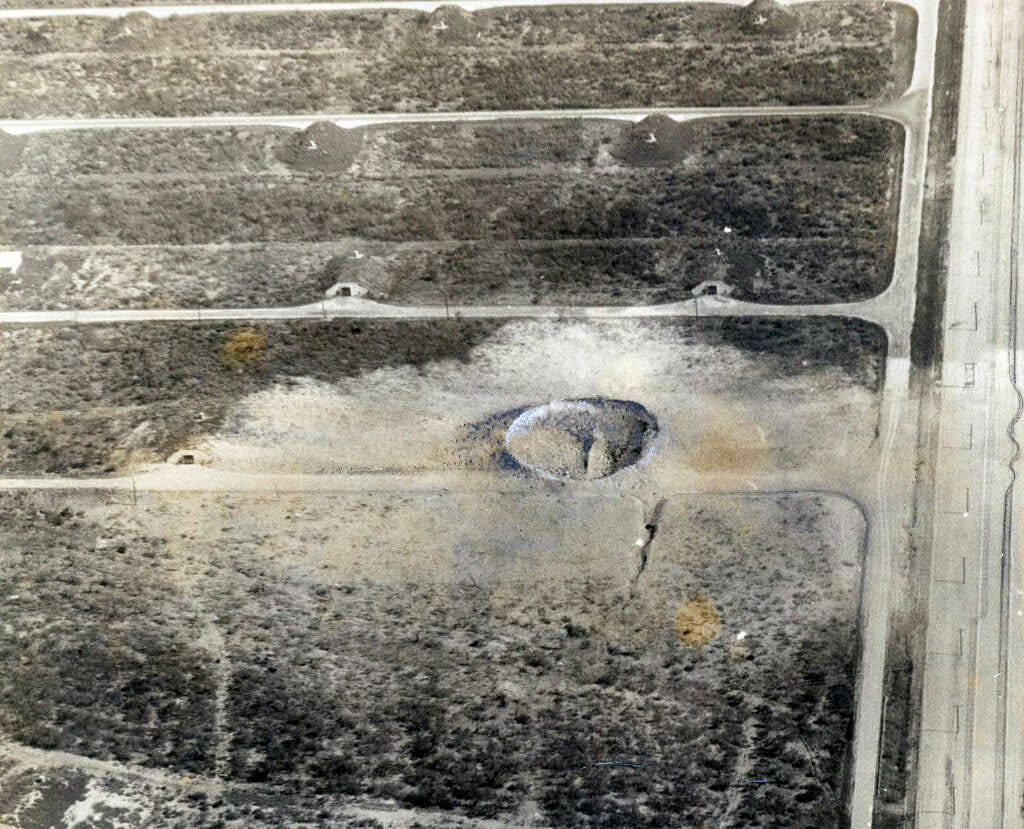

Part of the Lackland Air Force Base, the Medina Modification Center was one of the facilities responsible for dismantling, repurposing, and destroying nuclear and other hazardous weapons. Just imagine the dangerous payloads being transported around San Antonio—one of Texas’s largest metropolitan centers outside of Dallas and Houston. Those small structures, centered around what is now a massive crater, were called “igloos.” They housed some of the deadliest weapons imaginable, right next to the residents of San Antonio.

The explosion was so powerful that it literally "blew the phone out of my hand," recalled Doris Aguilar, a local resident who was a mile away from the blast. And what about the uranium likely scattered over the area? Newspapers quoted the Atomic Energy Commission describing it as "relatively harmless," "unharmful," and finally, just "harmless."

The damage was extensive, and public concern in San Antonio was high—citizens feared they were living amongst weapons of mass destruction (they were), and that they had been covered in uranium dust (they had). Yet, for good reason, the incident was soon forgotten. You can hardly blame Texans, or anyone else, for that.

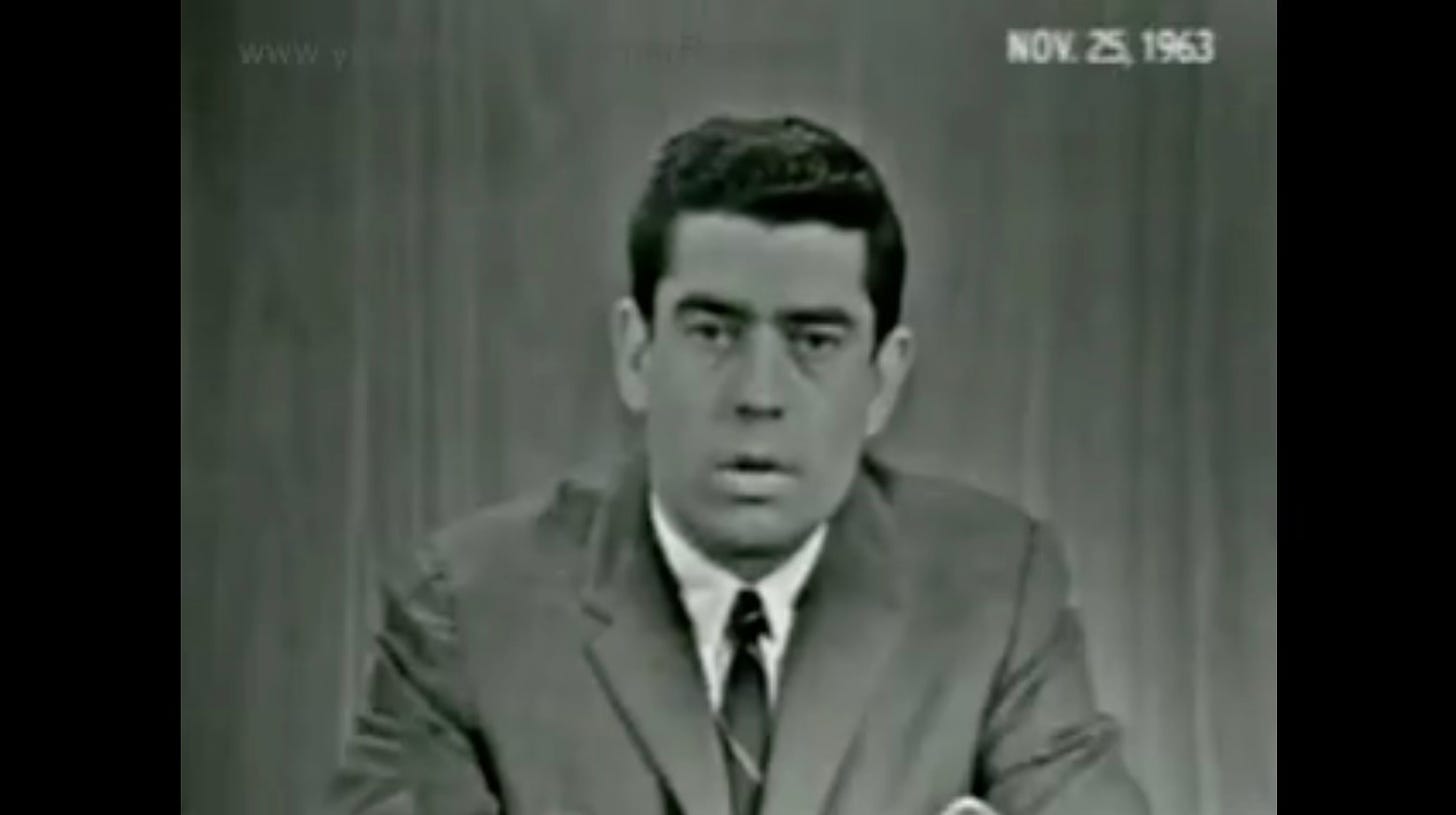

On November 25, 1963, Dan Rather took to the airwaves to discuss the Zapruder film—the now infamous footage of President John F. Kennedy’s assassination, which had occurred just two days earlier. Only nine days after the explosion in San Antonio, Rather was one of only two journalists to view the video of those fateful gunshots in Dallas. Another Cold War-era story ripe with conspiracy theories that Rather was tied to again.

Some things never change, including the news cycle. When one explosive event grabs the public and government’s attention, it can be overshadowed by the next big story—like the assassination of the president. There's no one to blame here, just a chaotic world that was as hard to navigate in 1963 as it is in 2024.

Reflecting on the explosion and its uranium dust so close to the public got me thinking: how often had nuclear accidents, or similarly dangerous incidents, occurred on American soil? I was in for a shock. It wasn't just accidents at storage facilities—the U.S. had accidentally bombed its own mainland more than once.

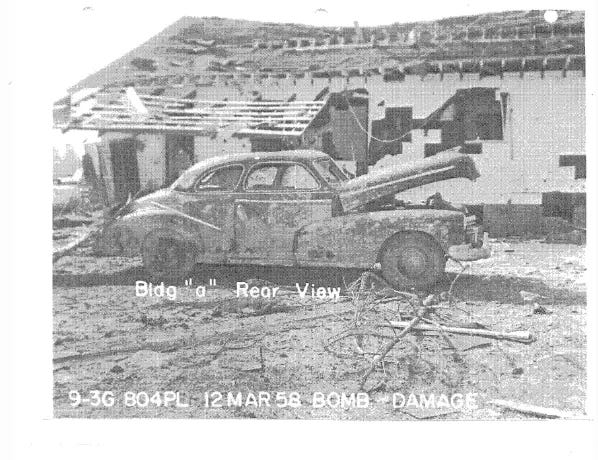

Take the frightening incident on March 11, 1958, over Mars Bluff, South Carolina. A crewman aboard a B-47 bomber accidentally grabbed the emergency bomb release handle, dropping an 8,000 lb. Mark 6 nuclear bomb. Though it lacked its core, the bomb was packed with two tons of high-energy explosives. The airman watched helplessly as it plummeted from the plane. It landed 50 yards from Walter Gregg, who was working in his garage with his wife and children nearby.

The blast was catastrophic, leaving a 70-foot crater and destroying much of Gregg’s property. The government dragged its feet in compensating Gregg, which didn’t surprise me at all. After all, Gregg was a U.S. veteran, a World War II paratrooper. And who better to screw over than a veteran?

“Veterans always seem to get the short end of the stick,” I muttered to Poppy, proudly displaying her paws, demanding a belly rub.

The paranoia of the Cold War era had built a massive war machine, one that ended up endangering its own citizens and soldiers. The reward for those involved? A lifetime of bureaucratic red tape when they sought healthcare or reparations.

“Maybe things will go better in Vietnam,” I grumbled, scratching Poppy’s fur, more to soothe myself than her.

As I dug deeper into these patterns, I noticed how frequently male overconfidence led to horrifying nuclear accidents. From ignoring safety protocols to disregarding warning labels, men with too much self-assurance kept making deadly mistakes.

The most extreme example of this hubris? The "Demon Core." A ball of plutonium used for atomic bomb prototypes, it became infamous after two fatal accidents. On August 21, 1945, 24-year-old scientist Harry Daghlian was conducting an experiment when he accidentally dropped a tungsten carbide brick onto the core, triggering a reaction. He was hit with a lethal dose of radiation and died 25 days later.

The second incident came about on May 21, 1946, when Louis Slotin decided to use a flathead screwdriver—in his hand—as a means to maintain a precise distance between two pieces of critical hardware near the core.

You can guess what happened. Slotin, who was known to wear a trademark cowboy hat and ooze bravado, had his screwdriver trick go sideways. With a flash of light, Slotin was blasted with radiation, along with others. He died from radiation poisoning nine days later.

Two deaths—likely more—because men were essentially playing "hold my beer" with nuclear materials. They had been warned, too. Fellow physicists had told them they’d be “dead within a year,” calling their experiments akin to "tickling the tail of a sleeping dragon."

The presence of a flathead screwdriver in these stories was as ubiquitous as the fish the descendants of these white dudes hold in their Tinder profiles, decades later.

In yet another incident, this time at a Minuteman I missile silo in Vale, South Dakota, maintenance workers found themselves troubleshooting a security alarm on December 5, 1964. Instead of using the proper tool—a fuse puller—a worker decided to improvise, jamming a screwdriver into the fuse box. This short-circuited the missile, causing its retrorockets to fire and eject the thermonuclear warhead.

The warhead fell to the bottom of the silo, prompting a delicate recovery operation. Where was it sent to be dismantled? Medina, at Lackland Air Force Base in San Antonio. Yes, the same place that had experienced a massive explosion just a year prior. Everything is fine. This is all fine.

The “how many men does it take to change a fuse” jokes practically write themselves.

As I continued reading through the history of nuclear accidents, a troubling realization took hold—how much waste and inefficiency accompanied these military efforts. Billions of dollars funneled into a narrow set of hands, enriching the brass that moved on to cushy jobs in the very industries they once contracted. The U.S. built over 2,000 XB-47 bombers, like the one that nearly obliterated Walter Gregg's home. These bombers dropped a grand total of zero bombs in combat before they were mothballed.

And guess who designed the XB-47? Boeing. What a surprise.

This endless cycle of upgrading weapons, retiring the old, and funneling money into military-industrial companies is maddeningly familiar. Whether it’s pulling a nuclear bomb’s emergency release or screwing with a thermonuclear warhead, the consequences are terrifying. Yet, the cycle persists.