Front Porch Digital Forensics

Trap beats, open loops and Dirty Daves spell trouble for our forensicators.

On the front porch of the rented house, I pressed my feet against the rail. They felt the rumble of an approaching trap beat before I could hear it. I closed the final pages of Chris Fabricant’s excellent “Junk Science”1 and looked up as the strange car on this strange street approached.

All of the occupants were hidden from view behind impenetrable tinted windows.

I tensed slightly.

My nerves were a bit frayed as I prepared to testify in a murder trial in a city far from my own. Days on end of reviewing the same crime, over and over. Reviewing the timeline and understanding the geography.

Heartbreaking for the victim’s family and the accused—generations of domestic violence, trauma and substance abuse.

In a different place and time, with layers of privilege and opportunity, this story could easily parallel my own. As a straight, white male, my path has often been cushioned solely by these pieces of my identity rather than any inherent merit or luck. Remove these layers; statistically, the outlook would likely be drastically different—perhaps dire.

I was also currently trying to ignore the fact that the events leading up to the murder occurred just up the street and around the bend from where I was staying. Places I drove past every day in my growing kaleidoscope of local Ubers. Places I peered at furtively, the odd emotional connection between crime scene photographs and the living world.

The trap beat car slowed.

I could hear the rapid ticking of the hi-hat through their high-end speakers.

Nice. A very tasty trap beat, indeed.

I pulled on my guilty-travel-pleasure, a Marlboro menthol. I reminded myself that this is precisely why an “imported” expert needs to stay in the community in which they intend to testify. It gives you a different perspective to know that your door can be blown off its hinges, just like in the case you’re reading, rather than being safely locked in a hotel on the 10th floor with security and police nearby.

No scooting out of town on the first flight for this guy.

I don’t think other experts should do it either.

I try to imagine what it’s like for a community member or family member who has to do this every day of their life. Testify, then live under a dark cloud of fear.

This is “method empathy” in my books, not an adrenaline-seeking activity. Go out and feel the vulnerability of the community, or stay the fuck home and write fiction instead. But don’t half-ass it in between.

Trap beat.

The car continued with no incident, followed almost humorously close by an elderly couple walking an even more elderly dog. The trio stopped to say hello and ask—

“Where are you from?”

That question could also prove deadly for the uneducated in a different neighbourhood at a different time.

Not so with these three as they waved merrily and ambled on down the tree-lined street that could have passed for the one I live on in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan.

I sighed and flipped my laptop open, heading to LinkedIn to try to make contact with a fellow Bullshit Hunter about the new, old junk science—the reason I was on this trip with my frayed nerves and quickly disappearing Marlboro menthols.

Digital forensics.

The new, old, not-even-junk, junk science.

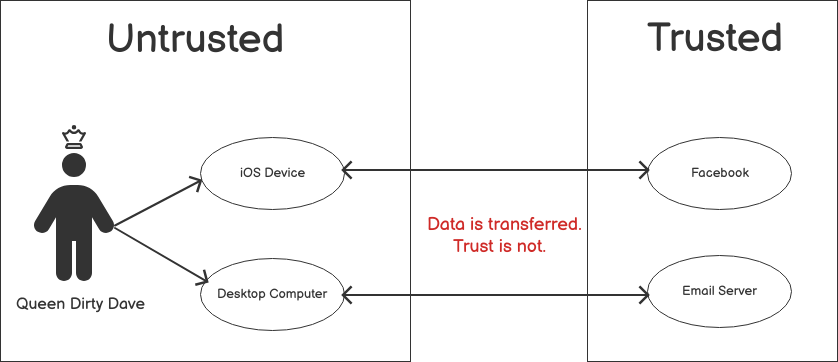

Data is Transferred. Trust is Not.

In the cybersecurity world, there are frameworks, quadrants and acronyms so long it would make your Mom blush if she saw them unshaven in a Polaroid. However, amongst the alphabet soup, one core principle is easy to understand as it relates to most2 criminal or civil investigations involving digital evidence.

Trust.

A very simple but often misunderstood concept. So, let’s go on a journey together with a fictional character in a fictional but relatable circumstance.

We have a guy named Dave. No, not our Dave. Never our Dave.

This Dave is a real asshole and loves to commit his crimes at work; in particular, he loves to stalk people using throwaway social media accounts, yank old passwords he finds on hacker websites to login to his coworker's social media and has a penchant for using his work phone and email server to send inappropriate missives and memes to colleagues and external parties.

He's also got a weird growth on his butt, and he likes to show it to people on various messaging apps non-consensually.

He's one of those Daves.

Through internal complaints and a human resources investigation, it's determined that Dave must be suspended while an investigation is performed to find out what the hell is going on.

Now, let’s say Dave has two devices: an iOS phone and a desktop Windows computer.

It really, truly, doesn’t fucking matter what these devices are. Call them a Blackberry and a TRS-80. Capichè? Don’t get hung up on the details, forensicators.

Dave has two primary services he used for his crimes: his work email account and Facebook.

Now, from the trust perspective, let's look at this nifty diagram.

So you may be wondering: Wait a second. Why are Dave's corporate phone and desktop considered untrusted? Aren't these ultra-secure, corporate-owned, and managed devices? Don't we have a chain of custody and physical control over them?

You can trust us, right?

Well, the thing is that Dave has put his sweaty, grubby paws all over those devices, and you have to assume that Dave has compromised, tainted, spoiled or otherwise fucked with the evidence, intentionally or otherwise.

If Dave's phone was a traditional murder scene, imagine his friends first using it as a skateboard park before your CSI team gets there.

How much could you trust the validity of the physical evidence after that? Is it completely ruined (I would argue it isn't), or does it simply need to be rigorously tested, sampled, and validated against other sources? You know, science things.

That's also why physical crime scenes are protected and guarded (with humans that have bullets and shit) to preserve their integrity. If someone messes with the scene or otherwise breaks the chain of custody, that's a problem.

Now, back to Dirty Dave.

You see, Dave is the master of those devices, regardless of the fancy tools installed by his IT administrator or security team. If Dave can access them and operate them freely? He's the queen. Queen Dirty Dave.

Thus? You can't trust the devices because you can never trust Dave. You have to verify every single statement and piece of evidence that Dave could have generated because Dave is greasier than goose shit. That's why we're all here today, after all.

You can't trust what he says, what his computer says, what his Blackberry says, or anything else he touches or does, really. He probably doesn't wash his hands.

So if the digital forensics performed on Dave's desktop computer shows that he sent an email with the subject line of "Justin is a Dickhead," dated June 1, 2023, 12:00:00, what do you actually know to be true at this point?

You know that his device generated forensic artifacts indicating that he sent an email at that time.

What you do not know is whether Dave sent it or not.

Or whether an email was sent at all.

Let's continue.

Placing the Person at the Keyboard

“Wasn’t me!” - Shaggy, in an ode to Eddie Murphy.

Numerous times, numerous crimes. We've heard the story repeatedly—something happened on a computer that was illegal, and the owner says it wasn't them.

It was their dog, their pervert cousin, someone else who had their Wifi password, a poltergeist, their weird neighbour or any other living or non-living entity that could cast doubt on them being the perpetrator, particularly with Child Sexual Abuse Material (CSAM) investigations, where the mere possession of the material is illegal.

In our Queen Dirty Dave case, the first thing you need to do is establish who was in care and control of that device at the time of the alleged "Dickhead Email." You should make sure you can put them there with eyewitness testimony, security card swipe logs, CCTV footage, login events, firewall, weblogs, etc. Correlate, corroborate.

You know.

Investigative shit.

This is now validating and verifying that you have a source of untrusted data generated by Dave. It places him at a device at a certain time and leaves forensic evidence (called artifacts, like in archaeology) on those devices. The more you can correlate that he was the one either physically or remotely operating that device, within reason, the better.

We still need to find out whether Dave actually sent a single email, logged into a Facebook account, or really much of anything beyond the untrusted evidence we have from his devices.

We know Dave was there, doing stuff on those devices, at a certain time.

So now we need to close this loop.

Closing the Loop

What we're now faced with is an investigative open loop.

We've got a lot of good theories and even some forensic evidence that Dave is up to no good. We even have fancy file hashes, some reports from expensive forensic tools and possess more pictures of Dave's ass than we could have ever wanted or needed.

It's a mole, not a wart, by the way. We checked.

What we don't have is a fully closed loop proving that Dave did what he is alleged to have done: sent some emails and fucked around on Facebook.

Quite simply—and this is identical in the journalism and intelligence world—we have to verify this against a trusted source.

We cannot simply change untrusted data into trusted data, like some data Jedi waving our hand over it and willing it to be so. What we can do is take trusted data (from the email server and Facebook), correlate it with the untrusted data and then try to pin it to the human in the chair operating the devices.

Where this scenario can change is if Dave was the administrator or owner of the email server. We now have to adjust that zone of trust to exclude the email server, and of course, as an investigator, it is up to you to find other sources of trusted data to correlate against now that he’s dirtied this one up.

Remember, if Queen Dirty Dave controls, administrates or has access to it, it's not trusted.

By retrieving the logs from the email server, filing subpoenas with Facebook (or warrants), and then correlating those trusted sources against the untrusted digital forensics and witness interviews, we bring the untrusted together with the trusted and match them to help show that an action, taken by a human, with a digital device, was most critically: recorded externally by a source outside of our control and outside of Dave’s control.

This is “closing the loop” and forms the proper backbone of a digital investigation3.

It’s been this way for decades4.

No Closed Loops. No Justice.

Imagine you did a DNA swab of someone, got their profile back (only theirs) and pronounced: "Yes. You are human, and I have your DNA. Thus, you committed this crime!"

I would hope that you are staring blankly right now or laughing. But this is exactly what happens all the time with digital forensics and digital evidence writ large.

In the case of DNA evidence, naturally, you need to take the DNA sample, explain how you obtained it, how you had legal authorization to do so, and what test you used to extract it. Then, you need to compare it against a database of other samples in order to authenticate it. For example, the sample at the crime scene, in a DNA database, or other sources that are outside of your crime lab.

That’s not what is happening with digital forensics in many jurisdictions. Half the time an examiner can’t explain how they got into a device to begin with5 nor can they explain how any of the blackbox algorithms or ‘carvers’ do what they do. Do they need to? I guess it depends. Case by case, as the saying goes.

However, in criminal and civil cases, both prosecution and defence forensicators, investigators and attorneys are presenting half of the digital evidence and convincing judges and juries that this is somehow different than swabbing someone’s cheek, shooting a three point garbage-shot with a Q-tip and declaring the person is the killer.

I have witnessed and reviewed cases where folks go into court and show digital forensics acquisitions, asserting that a plaintiff or defendant did or did not do something, never presenting correlating, trusted evidence to back it up. There are convictions based on that, too.

Judges, lawyers and jurors, not possessing a computer science background (generally), have no idea that they are being fed bullshit. I am sure they would truly care if it was a loved one who was about to spend the rest of their life in prison. I bet they'd get educated really quickly. I bet they would be a bit more skeptical.

Worse, often there are these long-winded arguments or bullshit Daubert hearings that focus on Faraday bags (sure they are important) and SQLite timestamps (also important, sure) instead of solid forensic investigation, verification and validation. Context is important.

You know. The work. A phone that's not in a Faraday bag is just as useless as one that is inside a Faraday bag if you never file a warrant to validate anything that's on it. You dig? Why are we even arguing about IOS timestamps and modification times when they aren't even being matched to an external source anyway?

Might as well make shit up.

I could care less what the timestamp on a SQLite database file says on Queen Dirty Dave's phone when Facebook's billion-dollar security infrastructure tells me down to the millisecond whether he logged on from a particular device and location and took action or not. If I can match that up to dirty, untrusted data that Dave controlled, I can close the loop on both ends.

An answer that doesn’t involve a black box, lying witnesses or eye-watering expert fees. No special dongles. No adapters. No AFU, DFU or GO-EFF-U.

Arguing over these tiny semantics permits clouding of the real, evidentiary and most crucial arguments in many cases. Preliminary hearings and expert certifications become a war of attrition: who’s going to run out of will and caffeine first?

I am certain this is not how any of this should be done.

The next time you're preparing for trial, a hearing, or any other legal matter, and someone presents you with forensic acquisitions or digital evidence that have no correlating data (warrant returns, subpoena returns, log files, corresponding digital acquisitions, etc.), make sure you call bullshit on them early and often. Cry from the rooftops.

Don't let it into our courtrooms, don't let our forensicators down, defend the science.

Don't put innocent people in jail with bullshit when you have the opportunity to quickly and easily close the loop with some paperwork and a handful of spreadsheets.

Epilogue

Slow-driving cars with trap beats. Travel fatigue. Days of relentless fourteen-hour shifts in trial preparation, with more to go.

Bone-weary, I laid my head down to sleep and closed my eyes. Drifting off to Brooklyn 99 softly playing on the smart TV tucked into the corner of the room before the sleep timer puts Peralta, Santiago and the 99 crew to bed too.

The screaming of a car horn, inches from my feet outside my window, in the dead of night flung me awake. I don’t know how long I was asleep, but there was no more Andy Samberg, no more Joe Lo Truglio.

Holy fuck, they’re back.

The trap beat.

I get my bearings in the dark, knowing it’s important to listen and orient before acting.

I’m waiting for the footsteps up the front porch and the inevitable crash as a boot clears it from its hinges.

The car horn is screaming continuously. It’s clearly intentional.

I may have bit off more than I could chew on this case. Fuck.

No footsteps yet. Time to start moving.

I pull back the covers and swing my legs off the side of the bed.

Then it stops. The last of the horn blasts softly, echoing away.

My ears are trained both on the window and the front porch simultaneously.

No footsteps.

No door crash.

And then—soft giggles of an elderly couple emanate only a few inches away from where I am perched at the edge of the bed.

Miss Neighbour leaned on the horn when she was helping her aging frame from her Prius.

If she wasn’t so nice, I’d ask her to do my newly soiled laundry for repayment.

So much for sleep.

Shit the bed indeed.

We recommended this book in Issue #23 of Weekend Warriors, Weirdos & Whackjobs:

https://www.bullshithunting.com/p/for-the-weekend-warriors-weirdos-2f3

It’s worth mentioning, and we will repeatedly, that Child Sexual Abuse Material (CSAM) investigations are the outlier here, simply because the mere possession of the material (it is found on your phone, tablet or computer) is a crime.

This works in both directions. If there are allegations that something happened on a server, you need to then work the opposite direction to find the devices, acquire artifacts in a forensically sound manner and then match them to the server.

Forensics Casefile: Catching the BTK Killer. https://www.forensicscolleges.com/blog/forensics-casefile-btk-strangler

This is through no fault of the examiner themselves, rather, it is the forensic software manufacturer who doesn’t want to disclose “protected techniques”, a commonly referred term used in law enforcement. Fair enough, I used to develop exploits. I get it, to a degree.