They’re a bit tiring, aren’t they?

Breach notifications.

In the year of our Dark Lord 2024, we are still bombarded with breach notifications or news of new ransomware gangs shutting down critical government services, schools, healthcare facilities or financial institutions.

It’s exhausting.

So, you’d think we’d be getting better at this, but we’re not.

On July 11, 2024, I sighed from some deep existential place within. I’d hopped onto Getting Out—the mobile application that allows me to communicate with prisoners in California—and was immediately met with one of those big ole glowing breach notifications.

Ok, so, kind of a breach notification.

I say “kind of” because for some strange reason, this particular piece of cybersecurity poetry indicated that the breach was four years old. No real explanation as to why I was receiving it on this day, and with a vague link to the “Rest of the Story,” as Paul Harvey would say.

I was left staring at this notification and wondering, “Do we not have a massive, multi-billion-dollar cybersecurity industry churning away at this problem? Are we still losing to the most basic shitty attack techniques?”

I dismissed the notification and sat back in my chair.

My mind flashed back to an advertisement I’d seen on Twitter earlier that week. Keanu Reeves appears in some weirdo science fiction action sequence that apparently represents a normal day at work for us nerds (no hate to Keanu, make your living, my man).

Zooming around doing Matrix-kung-fu is apparently an excellent way for a cybersecurity company to sneeze their limp-dick LLM-powered firewall onto the market.

Like Keanu-kung-fu would be a fantastic means to stopping a well-intentioned database administrator from causing a drag-n-drop catastrophe. Here’s looking at you extra hard, Palo Alto.

It won’t, like, ever—limp or not—prevent honest accidents.

It’s just so tiring to watch it all.

But I was a hacker for years, and I know: security is hard.

As a defender, you have to win 100% of the time, and an attacker only needs to win once. An attacker also, theoretically, has unlimited time and budget, no policy constraints and doesn’t give a shit about weekends, your mood or why your pharmacist didn’t refill your psychostimulants.

So, depending on how you look at it, the fight can be asymmetric in many ways on both sides.

But that doesn’t mean you don’t at least fucking try.

The best security practitioners and policy writers weave complex, unified, cross-team solutions that integrate humans, repeatable processes, code, algorithms, documentation, insurance, and lawyers. They relentlessly refine all of the above quarterly or yearly.

It’s hard, but when you actually try, you can prevent a lot.

When something bad happens, because it will, you will also do a much better job of protecting yourself, your assets, your customers and your supply chain.

This, my friends, is what we call “giving a fuck”.

The problem is that not many people actually give a true, full, honest fuck about cybersecurity. There’s just too much evidence to the contrary to argue otherwise.

One of my favourites was this open letter from famed short-seller, Carson Block, to Lemonade, a new-fangled insurance company launched onto the New York Stock Exchange during the batshit market days of 2020.

As a surprise to none, Lemonade, like so many other companies, doesn’t seem to care.

The vulnerability that Carson wrote about was so egregiously bad that Wolfpack’s Lead Analyst, Reed Sherman, said in a tweet that one of Muddy Waters’ security experts “was able to send me a PDF of my renter’s insurance policy less than 15 minutes after this was first discovered.”

“Short seller says Lemonade website bug exposed insurance customers’ account data,” May 13, 2021 - TechCrunch

Read between the lines, and you’ll see that the “security bug” is actually exploitable by clicking on a link in Google or the Wayback Machine, requiring no technical skill whatsoever. Technically, if you are viewing the records in Wayback Machine, that means their spider “exploited” Lemonade and “exfiltrated” sensitive data in order to archive it.

Funny, right?

From my understanding, Lemonade didn’t face any sanctions at all for this horrifying hole in their security, a hole that would make most insurance companies shit their policy-pants on the double and scramble for counsel cover.

Not one to miss out on the “Move Fast, Be Stupid” movement, Lemonade has since been stung with a $4-million class action over the storage of their biometric data.

Classic.

Solid.

*Fist pump*

Nailing it. Insure me, lemon-daddy. Underwrite me, sexy momma.

Now, all sarcasm aside, the real question becomes: as an investor, a journalist or someone about to attach their organization to an enterprise’s supply chain, how do I do a hygiene check of an organization’s cybersecurity breach response practices without touching breach data or being a technical investigator? How do I know how dirty this unit is before I climb into bed with it?

Follow along, friends. We’ll do it together.

Local & Federal Government Regulations

Referring to the Viapath notification published in July 2024, we see a few investigative details that indicate the breach was relatively small, with only thousands of records. Some of those records made their way to the grimy dark web, and Viapath (Telmate/GTL) notified various attorney generals in the United States.

This last part is a good thing if true. Breach notifications submitted to United States AG offices are generally considered public records, meaning we should be able to review them in most states.

In some States, they have taken a more proactive approach and built online databases that allow you to perform searches or find records related to the company and year of the alleged breach.

For the remainder, we have to do a little more legwork and write public records requests—the subject of Part 2 in this series, which you’ll read next week.

Let’s start with the government databases and see what we can find.

Searching State Breach Repositories

The International Association of Privacy Professionals has this handy list that you can use to find the States that include a searchable, online database.

So let's see what we can find, shall we?

California has the original breach notification sent out in 2021, with some additional details, including the breach being contained quickly and “all will be well with a little sugar, spice, and credit monitoring” la di da. They indicate that the breach was in the 'thousands,' which I would take to mean as high as 9,999 (or 19,999, if you like) but not 'tens of thousands.'

My brain jolted. Something was missing in this breach notification. The original notification submitted to the California AG in 2021 does not mention anything about the private data being posted to the dark web. They certainly mention it in the current breach notification in July 2024. So, does that mean that consumer data was exposed for four years, and they thought everything was cool? Or what?

This is a small inconsistency and strike one against them.Indiana has a slightly different online database with a clickable list of links that lands you in a PDF of a spreadsheet. What is incredibly useful is the spreadsheet gives us the size of the data breach in terms of number of citizens (or records) exposed.

Indiana's records show that there were 2,489 Indianans that were affected out of a total of 45,673 breached records. So now we have a pretty precise (allegedly) number of records that points out another small inconsistency, where we know it is, for sure, 'tens of thousands' not just 'thousands.'That's strike two against our prison phone friends.

Tip!

If the breach occurred in 2020, and the notification was in 2021, make sure you're searching for the year of the disclosure and the year of the breach itself. You should also look for any subsidiary or parent companies. Each database may list the notifications differently.

What we know is that the Telmate breach happened in 2020, was reported in 2021 with no dark web dirtiness, and included tens of thousands of records exposed that, four years later, ended up on the dark web.

The unclear number of exposed records and inconsistencies in the language still leaves some pretty critical questions.

Thousands? Tens of thousands?

What's next? Hundreds of thousands?

Millions?

What about that whole dark web piece?

The Federal Trade Commission

The Federal Trade Commission is the main consumer watchdog and civil regulator in the United States. They are the ones who will, generally, but not always be involved in litigation if a company has mishandled data or done bad shit to kids online.

A simple Google search for the company name and the FTC website will usually yield results, if there are any. You can, of course, go directly to the FTC.gov website and use their search bar as well. Go nuts.

In this case, we hit some very unexpected pay dirt.

Ho, Dolly! Looks like our friends are deep in it now, with a civil complaint filed in 2023 and another or an amended complaint filed in 2024. The FTC is pissed. Let's break down some of the most fun reasons why:

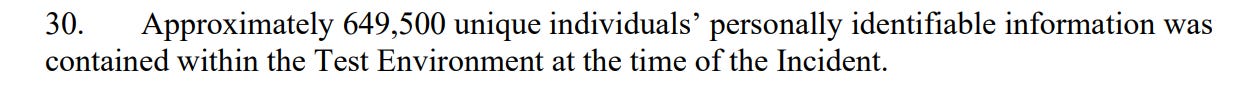

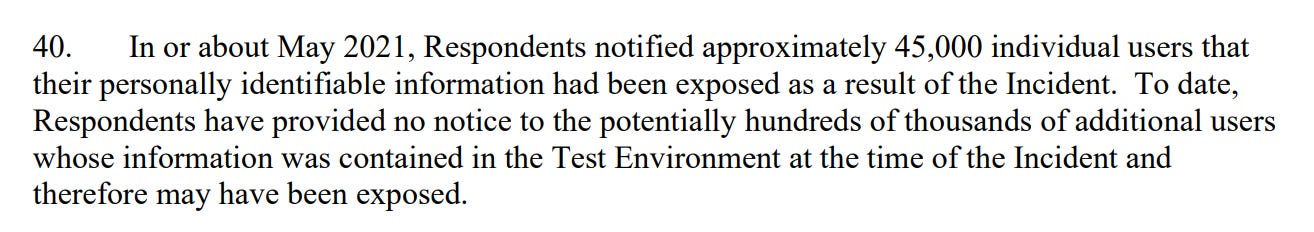

Uh oh. We went from thousands, to tens of thousands, to hundreds of thousands. The news only gets worse.

Holy shit. Imagine all the members of the public communicating with all of those prisoners. We're talking journalists, politicians, advocates, family members, celebrities, lawyers, spies. This would be an absolute trove for bad actors, depending on the facility and the parties.

This, to me, is actually a national security concern that should probably be investigated, too.

Pshew. Read on, good soldier. It gets worse.

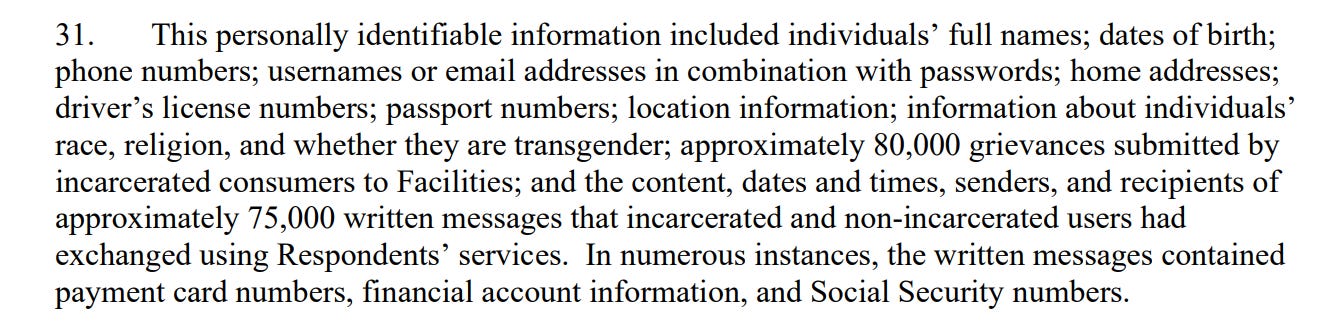

So, the breach occurs in August 2020. A few weeks later, in September 2020, a company reaches out to tell them that the data is allegedly on the dark web. GTL then works to confirm that it is, in fact, their data. However, we don't get a breach notification until much later, in 2021, and there is no mention of the dark web, as previously pointed out.

Hang on, now. Just a minute here. We are in November 2020. Consumers are complaining that their information is showing up on the dark web, and we still don't have a public breach notification. What is going on?

Oh boy, almost a year later, and just now, they are notifying 45,000 people. This matches our research from Indiana, which gave us 45,673, but it's only 7.03% of the total records that were actually breached.

So, are they lying? Or did they simply not know how much data was breached?

Those three paragraphs allege that not only did Telmate misrepresent the breach, but they carried on peacefully, winning contracts (I believe from the US government) while being dishonest about the state of their security, something that would definitely have an impact on scoring contracts. Big time.

Per the FTC's complaint, Global Tel Link churned $600 million USD in revenue.

I would say that answers it.

In my opinion, this is not the behaviour of an honest company looking out for its consumers, users, inmates or even themselves at this point. How much of that $600 million in revenue was won without being transparent about the full state of their cybersecurity?

What else are they not being truthful about?

You're encouraged to read the remainder of the complaint and associated documents to your heart's content.

*dusts hands*

That was fun, and we’ll leave it here for now. The next step will be to try to find more records that aren't publicly available in searchable databases by sending carefully crafted public records requests. That will be for next week, friends.

Wrapping Up

I have found that breach research (just like consumer research) is tremendously useful for sniffing out fraud of various types.

Security is hard, but due diligence on your enterprise partners, providers, and RFP submitters is not.

Our team's countless hours of research into public and private companies have shown this: It is a big ole red flag if you leave your data zipper down, open and proudly walking around... *looks down*… that exposed.

Until next time, I recommend practicing your time-lining skills on this case because it's an excellent exercise.